This blog post is written by Jennie Barron, Professor at the Department of Soil and Environment; Agricultural water management, SLU

Water is a multifaceted resource from simply being served our daily glass of water, to the complex flow through the landscapes to produce food, recreation and other ecosystem services. Because of the multiple uses and benefits of water, there are many challenges of valuing and weighting benefits and impacts for the different uses and users.

This becomes evident in times of shocks and in crises. For example such as when the landscape or society runs out of water, as in the extreme drought of 2018 in Sweden, or when 2 billion of people lack health and sanitation facilities to simply wash hands to cope with COVID-19. The past years global and local crises of COVID-19 has left no one untouched. And the crisis of COVID-19, has really reoriented the issue of conversation of water, and the value of water.

The projections of water related crises is on the rise, as food security, sustainable development and climate change takes place. The need to find metrics, process and practise to weight the benefit and impacts of water scarcity will therefore be the key. This year’s World Water Development Report is thus a first step to summarise and synthesise the current perspectives on valuing water. It builds on the recent developments such as the High Level Panel of Water Statement (2018) “Every drop counts” and assessments on water security for food and nutrition by FAO (2020) “ Overcoming water challenges in agriculture“.

Going from high level statements to reality and practise

Agriculture is such sector that is an intense water appropriator globally, both in using rainfall, and extracting water for irrigation. In addition, agriculture can have a negative impact on water quality, as a source of agro chemical pollution both from crop and livestock production. Valuing water for irrigation is a particular challenge, as the fresh water from surface and groundwater sources is contested for many users, including the environment, aquatic benefits and food. However, in regions where many people are affected water scarcity and hunger, the value water might bring into agriculture can make significant livelihood improvements. For example in the work assessing benefits for smallholder farmers in the dry area of Bundelkhand , India led by Garg et al (2020), evidence-based soil and water innovations introduced, improved landscape water use and the farmer incomes by up to 170%. At the same time downstream water availability reduced with 40% in a normal rainfall year. Here a dialogue on upstream benefits and values, may need to be negotiated with downstream users. In a case of livestock systems intensification in Tanzania (Noetenbart et al 2020), choosing the most resource saving option of intensification can have negligible impacts on water use. For example a comparison of livestock production accounting for water appropriation into the fodder, showed that extensive dryland grazing could only marginally increased total water appropriation, whilst improving water productivity with 20-50%, when combining animal health, breeding and feed options. Here the most water demanding livestock scenario was the system with import of high protein (and more water demanding) fodder crops.

Investing to secure water for agriculture is an enabler of development.

Globally, about 40% of food comes from irrigation-dependent crop production systems, helping to support nutritious and all year food supply. Whereas regions and countries are running out of water, we have other regions that could better support irrigation development to adapt to weather extremes and bring both steady supply of food and nutrition and income. In Sub-Saharan Africa, less than 3% of the crop area is under formal irrigation. Yet smallholder farmers are evolving and investing themselves in so-called farmer led irrigation, despite a number of technical , social and financial challenges (Lefore et al 2019).

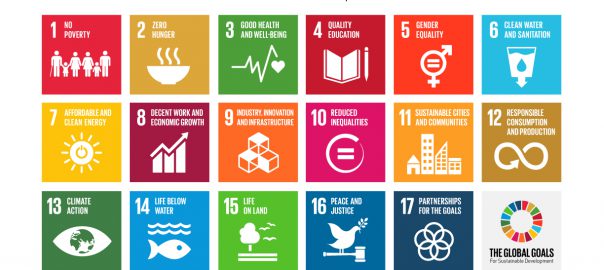

It is becoming evident that water is a critical enabler in development and Agenda 2030 for human health, incomes, food and nutrition as well as ecosystem services. Water needs to be bothsafeguarded for multiple benefits, as well as negotiated and explored in some cases, for additional uses in anthropogenic landscapes. By opening for reflecting multiple values, we can develop data, tools and weight benefits and trade-offs more just and equal among uses and users. In 2022, it is the +30 years of the Rio Declaration (UN Earth Summit 1992), including the statement of Integrated water resource development (IWRM) Let’s hope that water is back on the agenda for enabling development as, carefully negotiated for its multiple use and value.