This blog post is written by Anneli Sundin, Communications Lead in the AgriFoSe2030 programme. This post was first published by SEI.

Theory of Change (ToC) is a systematic approach focusing on pathways to change. This approach can be a key ingredient for a well-functioning project design, blended with stakeholder participation and strategies for communication. Here, three takeaways from a recent paper exploring the use of ToC are outlined.

We still see food and nutrition insecurity in many parts of the world and, in recent years, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of Zero Hunger (SDG2) seems to have become more difficult to reach. To combat this challenge, smallholder farms need to further increase their productivity.

We in the Agriculture for Food Security (AgriFoSe2030) programme believe that we need to connect and synthesise best available scientific research with policymaking processes, as well as with practices on the ground. We focus on sustainable intensification of smallholder farming systems in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South and Southeast Asia for improved food and nutrition security and are interested in bringing change that directly benefits smallholder farmers. But we need tools that can guide us. As such, we turned to Theory of Change.

In the recently published paper in the journal Global Food Security, we showcase how we applied Theory of Change in three projects. It is an approach for evaluation, widely used today within development practice, and, stated in the paper as “a systematic way of clarifying the underlying theories and cause-effect pathways that underpin initiatives working to promote social and economic change, particularly in complex interventions”, such as those interventions that take place in agricultural research for development.

All of the three projects were part of the wider AgriFoSe2030 programme, and aimed to translate research into policy and practice. The paper explores the benefits of having used ToC in the projects, as well as some of the challenges it involved.

The projects

All three projects are related to different types of livestock production in low-income countries. One of them looked at how to develop the sector for edible insects as a way to combat food insecurity in Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Another one, based in Uganda, further north in SSA, focused on sustainable dairy production and artificial insemination. The third project was about improved goat keeping for smallholder farmers in a number of different regions in Laos, Southeast Asia.

Here, three takeaways from our paper are outlined, exploring how to enable a successful ToC process. At the bottom of this page, you can read more about the ToC stepwise method.

Takeaway 1: Stakeholder engagement as you begin your ToC

Many research studies have shown the importance of stakeholder engagement for a successful research or development project. Throughout each project period, the teams focused on activities that involved reaching out to stakeholders and finding inventive ways to engage with people. For instance, the groups involved stakeholders outside academia from the onset of the projects. The paper states that “drawing on all stakeholders’ perspectives, experience and skills to construct the ToC map strengthened the shared vision, identified the key target groups and developed a realistic ‘pathway’ to guide planning and implementation”.

Through this genuine and early stakeholder engagement, the projects gained wide support early on, which manifested in tangible outcomes in the longer term. For example, in the edible insect project, representatives from the municipality of Chinhoyi in Zimbabwe were part of the project team, and understood through their participation the value and importance of boosting the edible insect sector. As a result, they decided to devote a piece of land to the construction of an insect market facility.

In the example of Laos and goat management, a strong feeling of ownership of the project and its goals was created among the agricultural extension officers (the intermediaries between farmers and researchers), thanks to robust collaboration between the researchers and extension agencies. This also resulted in the project reaching farmers more easily.

Takeaway 2: Allow for flexibility

When we made sure that there was good internal communication within projects, and also between projects and both the AgriFoSe2030 management and the communication and engagement team, everyone had a better understanding of the contexts in which the projects were operating. Hence, it was easier to redirect funding and resources in ways that helped achieve the projects’ desired outcomes. This allowed the project teams to adjust their ToC plans. Previous research points to this as very important for success; in order for them to succeed, projects need to have some degree of flexibility in budgeting and resources, and there is a need for “complexity-aware” approaches.

Takeaway 3: Combine your ToC with communication strategies

In each case, we gave the project teams training and guidance in how to communicate with relevant stakeholders. This covered, for example, how to explore windows of opportunity, and how to tailor speeches, presentations and written texts so that audiences would not just understand, but also listen to them and become interested and involved. The projects used planning matrixes for their communications, in which they mapped specific stakeholder groups, the change they were targeting for that particular group, what messages would work well and through which channels they could communicate them. The projects also made sure these matrixes were aligning well with their ToC plans.

It’s not all rosy – but the benefits outweigh the challenges

The projects did also experience some challenges. It can be difficult to learn the ToC approach if you’re completely new to the concept. It was important to de-mystify it and have a facilitated process with a ToC expert, from start until the end.

The two projects on the African continent aimed at going beyond improving practices to also influence policy. They realised that policy development on governmental level is often a slow and fluid process. Sometimes you rather need bottom-up approaches that can demonstrate clear results. They decided, therefore, to get closer to local policy processes. When a policymaker can clearly see that an activity or initiative is successful on local level, it can open up opportunities for policy changes on regional or national levels.

Early in the process of developing their respective ToCs, the project teams understood that creating associations with their target groups (e.g. the farmers, traders or extension services) would help in consolidating the projects, as well as spreading knowledge and experience to a wider group. However, all three projects struggled with launching these farmers’ or traders’ associations due to the short project periods and contextual challenges linked to “e.g. demographics, the institutional landscape in which the associations operate, the environmental context, as well as underlying economic structure or local economic base”.

However, thanks to the early involvement of stakeholders and the fact that some of these associations could create demonstration farms, spin-off effects could be seen. In the case of dairy farming in Uganda, both an association of AI technicians was formed, as well as a number of farmers’ associations. These activities led to the renewal of the animal fertility and breeding centre at the Makerere University, and AI skills training is now included in the university’s educational programs.

We are yet to see the long-term impact of these AgriFoSe2030 projects, but we understand that ToC has helped them to more effectively integrate science-based knowledge in agricultural practice and policy. When we engage with stakeholders and develop refined communication strategies as part of our ToC planning, we will increase the likelihood of getting on the right path to impact.

What are the steps in a ToC process?

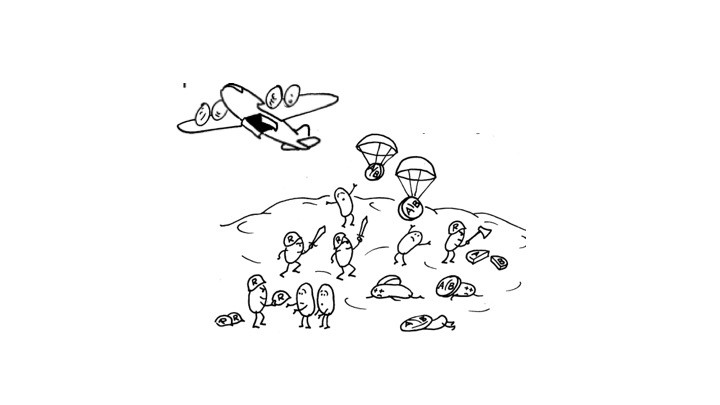

These projects walked through an eight-step process, guided by a ToC facilitator. This process begins with understanding the purpose of using ToC methods and describing the desired change, as well as the current situation. It then continues with the identification of what, where and by whom change needs to be made, and with the mapping of change pathways. Thereafter, strategies are developed for the interventions needed to make that change happen. Last but not least, it is important to look at monitoring and evaluation of the project and reflect on the full process. See the figure below to get an overview of this stepwise approach.

Read more about the AgriFoSe programme here

AgriFoSe2030, Agriculture for Food Security, contributes to sustainable intensification of agriculture for increased food production on existing agricultural land; the aim is to do so by transforming practices toward more efficient use of human, financial and natural resources.