This blog post was written by Tilde Lindbäck, student at the Master of Agriculture Programme – Rural development, at SLU.

Picture1: The two study sites in which the thesis was conducted.

As I am writing this blog post, I just got back home to Uppsala after spending approximately 10 weeks in Nepal, collecting data for my Master’s thesis. In spring 2025, specifically between February and April, I received a Minor Field Study scholarship, financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, to conduct part of my Master’s thesis in Nepal. Thanks to my supervisor I was hosted as a guest student at the South Asian Institute of Advanced Studies (SIAS).

My journey to Nepal began in Kathmandu, where I spent the first two weeks in the SIAS office. During that time, I met colleagues and the interpreter I was going to work with. After I had started to familiarise myself with the context and received some input from local researchers on the research topic, it was time to head out into the field. Leaving Kathmandu was something I had longed for, not only to start interviewing farmers, but also to get the chance to see more of the beautiful landscape of Nepal and escape the hectic city life in the capital.

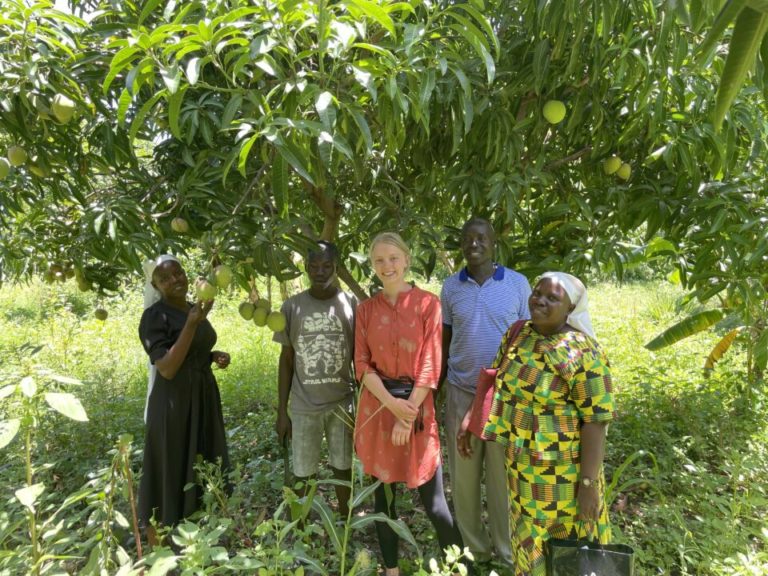

The first study site I went to was in a dry mountainous village in Mid-Hill Nepal, located in the district of Ramechhap, and the second study site was a green and lush village in the neighbouring district of Dolakha. During the daytime, we were out talking to farmers, conducting both formal interviews and casual conversations, or participating in everyday life activities such as grazing animals or attending community meetings.

A key finding was that intersecting identities shape what just adaptation looks like for different farmers. For example, uneducated female farmers were often excluded from public meetings where resources like drought-resistant seeds were distributed. Although these forums were formally targeted at women, structural barriers such as illiteracy excluded many from participating. Thus, the thesis could reveal that barriers to adaptation are not only gendered but also differentiated among women themselves. It challenges the assumption of a homogenous female experience and underscores the need to recognise how gender intersects with education and other social markers to understand differentiated adaptation. This example illustrates gaps in both procedural (decision-making) justice dimensions, as certain groups are excluded from decision-making processes. As well as distributive (economic) justice dimensions, where resources are unequally shared. It may also contribute new knowledge to feminist and climate justice literature by showing that female farmers are not a homogenous group, but rather experience adaptation in diverse and unequal ways.

Having the opportunity to conduct my study in two villages was not only good for generalizing the material and understanding how local conditions shape adaptation outcomes for farmers, but it was also very insightful on a personal level. Since I had never been to Nepal before, I had many new things to learn. Experiencing the differences between the two villages gave me a better insight to the living conditions in each village.

Patience was something I really needed to practice while travelling in Nepal. Since the infrastructure is not as developed as in Sweden, travelling by public transportation usually takes a few hours. On our trips with public vehicles such as buses, I was always surprised by the goods loaded onto the buses. Sometimes the bus driver would stop to pick up some chickens or load some goats onto the roof of the bus.

Picture 5: Different participatory data collection strategies were undertaken.

My experience of conducting fieldwork in Nepal has been fantastic and I would strongly recommend it to any other students who are interested in learning more about a new country, culture and people. I have been able to gain rich material and in-depth knowledge of intersectionality, justice and adaptation in Nepal. I also had the chance to do some travelling within the country. The travels I did included a 10-day trip at the end of my time in Nepal, as well as shorter weekend trips with my interpreter, who would invite me to her parents’ house, take me to Hindi festivals and different hikes.

Lastly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Dil Khatri, my interpreter, Miss Jeni Dahal, and my local supervisor, Mrs. Guyanu Maskey for your support, comments and knowledge on the research topic. Besides that, I also want to thank Sanyaja Khatri and the rest of the colleagues at the SIAS office who facilitated to coordinate the fieldwork. A big thanks to my family and friends for their emotional support, patience, and belief in me. I also want to thank Bibek Tamang who became my personal driver and a good friend during my time in Kathmandu. One last thanks to SLU Global for the Minor Field Study grant that facilitated my travel and research activity in Nepal.