This blogpost is written by SLU students Emma Bergeling, Hanna Smidvik, Emil Planting Mollaoglu and Felicia Olsson. It was first published by SIANI.

As a result of the corona pandemic, the embedded practices of international travel in academia drastically changed. It suddenly became customary to replace business trips with digital alternatives whenever possible. Four students at SLU decided to study the implications. The results show a great untapped potential to reduce emissions from academic travel by conducting a larger share of academic activities digitally – without compromising the quality of research.

In the turmoil that arose due to the travel restrictions put in place in March 2020, academics suddenly had to find solutions to continue their work in ways that did not include longer business trips. As students actively involved in discussions on universities’ greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, we have for long been discussing the question of how academic business trips can be replaced by digital alternatives while maintaining the quality of work and research. 2020 presented an unexpected window of opportunity to seek an answer to that question and to gather academics’ experiences of the new reality without travels.

Academia in a burning climate crisis

The topic of GHG emissions from academia in general and academics’ air travel in particular has over the past decade been the focus of a growing number of publications in scientific journals and in mainstream media. This should be understood against a backdrop of factors such as i) the climate crisis itself, ii) the notion of aviation as one of the fastest-growing sources of GHG emissions – characterised by a slow technological development unlikely to compensate for the estimated growth in demand, and iii) the recognition of academic researchers as among the highest emitters when it comes to international air travel, but also as potential leaders in a transition to a society within the planetary boundaries, if combining advocacy with changes in their own emission habits. This debate has resulted in various commitments, initiatives and responsibilities for higher education institutions (HEIs) around the world. With air travel being one of universities’ largest sources of GHG emissions, the need to critically scrutinise the norms and practices of academic travel is apparent.

Prior to the pandemic, one could mainly speculate about the consequences of a drastic and large-scale reduction of travel in academia. University employees’ recently gained experiences of an increased use of digital solutions replacing longer business trips are therefore valuable in the search for new norms and practices of academic travel. In our study, we wanted to collect these experiences before they fell into oblivion. Through 25 semi-structured interviews and a survey with approximately 220 respondents, we sought to answer how employees at SLU experienced the cancellation of business trips and increased use of digital solutions. What trips worked well or not so well to replace? How was the quality of various academic activities (seminars, thesis defences, conferences, project meetings etc.) affected by being held digitally?

Digital solutions replacing academic travel – what have we learnt?

Our study shows that there is a great, untapped potential to reduce emissions from academic travel without compromising the general quality of the research and work. By adopting a more thought-through mix of digital and physical meetings, where a larger share of activities are conducted digitally, academia can reduce GHG emissions while keeping the quality as well as opening up for greater accessibility and participation.

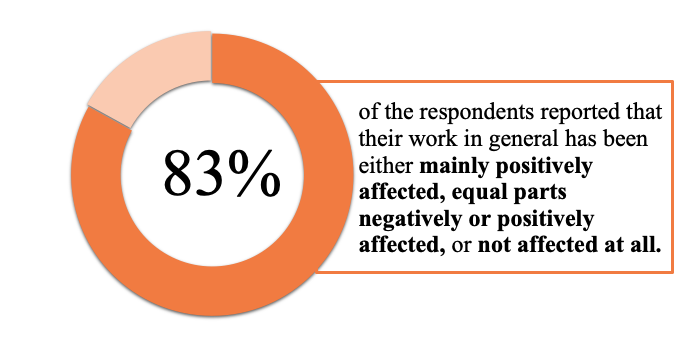

A majority of the respondents were surprised by how well it had worked to replace longer business trips with digital alternatives, surprisingly well or beyond expectation were common formulations. An overwhelming majority (83%) of the survey respondents reported that their work in general had been mainly positively affected, equal parts positively and negatively affected, or not affected at all by the travel restrictions.

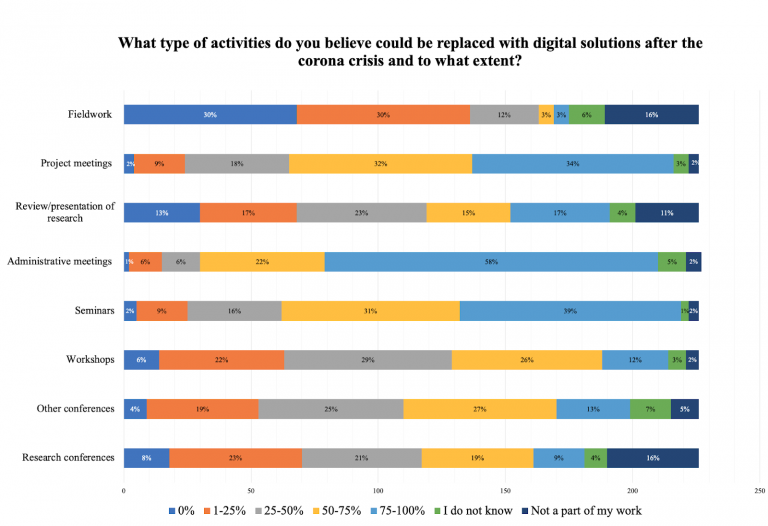

The academic activities that were experienced as most difficult to perform digitally were certain types of fieldwork and data collection, as well as activities that require spontaneous discussions and networking. We also found that meetings had become more efficient, but often at the expense of social interactions. On the other hand, well-structured meetings with a clear agenda between people that had previously met in person, as well as activities such as administrative meetings, project meetings and seminars, were perceived as most suited to perform digitally. These experiences were also mirrored in the survey respondents’ answers to what academic activities they thought could be held digitally – and to what extent – in the future.

Furthermore, our results show how digital activities have enabled greater accessibility and equality within the academic community. Researchers that would not have had the time, resources or possibilities to travel to various meetings could now participate in digital events on more equal terms. On the other hand, lack of access to stable internet connection and issues of time differences made certain meetings less inclusive and/or equal. A key takeaway is therefore that digital events have the potential to be more inclusive than physical events but that it is important to actively consider equality and accessibility aspects in planning.

Another eye-opener following the increased use of digital solutions is how these were used to reach a wider audience with research and education. Instead of having farmers or beekeepers travel to SLU to listen to a seminar or to take part in a course, the material was recorded and made publicly available digitally. In a research project reference group consisting of farmers, more had been able to join the meetings now that they were held digitally, as opposed to before when the group had to travel to SLU for each meeting.

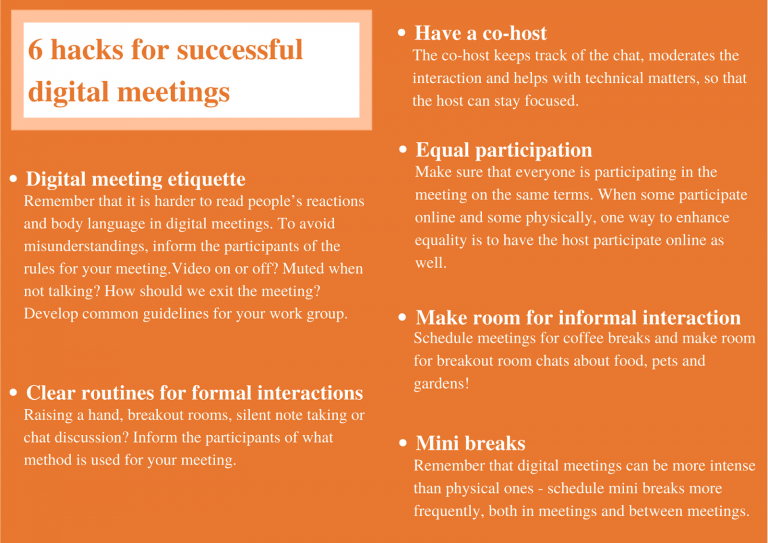

Our study also found that there seems to be a need to improve how we use digital solutions and start thinking beyond the mere translation of a physical event or meeting into a digital one. The informants had a lot of useful insights concerning this and we have summarised some of these insights in the figure below.

Lastly, most informants lacked experiences of networking in digital events as this part had been neglected when events were digitised and they stressed a need for new and inventive ways of networking digitally, moving forward.

New ways forward for academia post-corona

The participants clearly did not want to continue travelling to the extent they had before the pandemic. However, no one wanted to completely move from physical meetings to only digital solutions. It is time we find a golden middle way. Many expressed that they had begun to think in new ways about what makes it important to meet in person and what makes a business trip necessary or not.

“I’m sure you can reduce the amount of physical meetings quite considerably, and that the [physical] meetings you do have you can spend some more quality and preparations at them so they are well motivated and so that you get the most out of them. ‘Which are the good conditions and perks of meeting in person?’ And then make sure to optimise them.” – Professor

Although the pandemic has closed countless doors, it should in some respects be seen as a window of opportunity to make new decisions and do things in new ways. An opportunity to address and rethink what is actually possible in terms of reducing academia’s GHG emissions.

“There are surely plenty of ways to do this that we have never tried, that might be better than what we are doing right now.” – Professor

Interesting questions remain: what will university managements as well as researchers make of this opening, what insights and new learnings will they bring with them into the future? Which new practices will stay on to become embedded within the culture of academia in a post-corona context? We argue that the answers to these questions should lead to emission reductions in line with climate science. That decisions about what business trips actually are necessary are based on thorough evaluations of experiences from this pandemic, and that digital solutions are used strategically to replace longer business trips. The urgent climate crisis, combined with this unexpected window of opportunity, makes it crystal clear that the time for academia to change embedded practices, rapidly reduce emissions and take on a leadership role is now. Our study has shown that all of this can be done without compromising the quality of research. So what are we waiting for?