– A Master’s thesis about Swedish carbon offsetting initiatives through tree planting projects in the Global South.

This blog post is written by Emil Planting Mollaoglu, Research Assistant at the Department of Urban and Rural Development, MSc in Rural Development at SLU

Over the past two years, I have studied the Rural Development and Natural Resource Management Master’s Programme at SLU. During the spring and summer of 2020, I wrote my Master’s thesis – which focused on the role of companies and consumers in mitigating climate change. More specifically, the thesis explored how two Swedish companies, MAX Burgers (MAX) and ZeroMission, presented carbon offsetting on their websites. MAX is a fast-food restaurant chain that has received a lot of attention for its engagement with climate change and ZeroMission is an intermediary company that sells carbon offsets to MAX and many other Swedish and Scandinavian businesses. Through interviews with customers at MAX, my thesis also explored how carbon offsetting was perceived by a sample of Swedish consumers. The thesis illustrates how planting trees in Uganda has enabled MAX to communicate to its customers that they will solve climate change by eating at their restaurants – in spite of the company’s yearly increase of greenhouse gas emissions.

In recent years, many Swedish companies have voluntary made commitments to reduce their climate impact. An approach adopted by several Swedish food and beverage companies (among others) to lower the impact is to offset their greenhouse gas emissions. This is commonly called “carbon offsetting” and it means that emissions occurring in one place are compensated for by reducing emissions or storing carbon somewhere else. This is done through projects producing carbon credits – for example through capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by planting trees. The carbon credits can then be traded on carbon offsetting markets as a way for people, companies, organisations and governments to offset their negative climate impact.

Although it may sound good that actors offset their climate impact, carbon offsetting by planting trees in the Global South is not without contestation. Critique has for example been raised regarding uncertainties of the permanence and additionality of projects. These are two of the conceptual pillars of carbon offsetting. Offsetting projects are also meant to deliver sustainable development benefits to stakeholders in the Global South, and yet, there are documented cases of a lack of such benefits and even of negative impacts on communities. In addition, so-called natural climate solutions (such as forest preservation) and methods for carbon dioxide removal (such as afforestation) are not infinite. To meet the targets of the Paris Agreement we need these tools for negative emissions to counter the impact we already have had on the climate. Researchers have therefore argued that we should change how we think about carbon offsetting and move away from the idea that we can compensate for continuing to emit greenhouse gases.

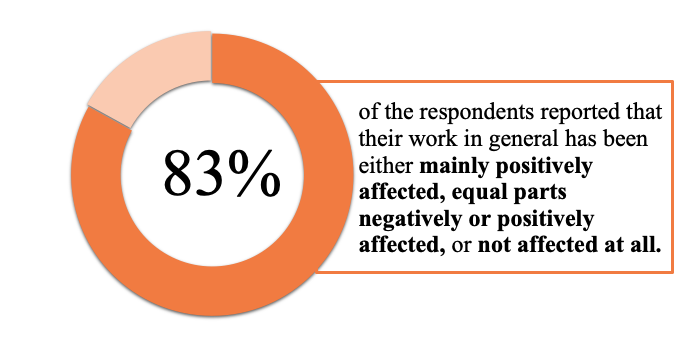

Since 2008, MAX has been offsetting 100% of its emissions through Plan Vivo certified tree planting projects – mainly in Uganda. Since 2018, the company has expanded its investments in planting trees and now offsets 110% of its emissions. MAX calls this approach “climate-positive” because the carbon offsetting extends beyond the company’s own emissions and captures an extra 10% of CO2. The Swedish company has gained international recognition for this approach. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has praised MAX for introducing the world’s first “climate-positive” menu and in 2019 the company received the UN Global Climate Action Award, which was presented at the UN Climate Change Conference in Madrid.

The results of my thesis show that the two companies describe climate change as a problem of both reducing emissions and removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but that MAX’s emissions have continued to increase on a yearly basis. My analysis also show that the companies highlight consumption as a cause of climate change, but that the “climate-positive” approach attempts to turn consumption into the very solution to the problem. In this regard, a lot of responsibility for solving the problem was put on consumers, who were expected to choose products and companies based on their climate impact. The two companies also highlighted that deforestation is a major cause of climate change and that companies within the food industry in particular are part of causing deforestation. The argument here was that deforestation occurs as a result of land-use change, from forest land to agricultural land for cultivation of food crops. Both MAX and ZeroMission therefore argued that companies within the food industry have a responsibility to counter the loss of trees by planting new ones. The final theme of the analysis emphasised how carbon offsetting was represented as a solution to sustainable development challenges in the Global South.

The thesis concludes that all the abovementioned representations reinforced each other and created a strong narrative for offsetting by planting trees in the Global South. At the same time, the customers’ responses implied that the view on how private actors and individuals can mitigate climate change is not homogenous, as they partially contrasted the two companies’ representations of climate change. The customers’ responses also illustrated a mental distance to the tree planting project in Uganda. This was for example apparent as one of the customers expressed that they did not understand the connection between MAX in Sweden and a tree planting project in Africa, but that “planting trees is always good”.

Finally, and as mentioned above, the thesis illustrates how a lot of responsibility for solving the problem of climate change is put on the individual consumers. Planting trees in Uganda has enabled MAX to communicate that climate change will be solved by its customers, that choose to eat at the Swedish fast-food restaurant chain instead of somewhere else, in spite of the company’s yearly increase of greenhouse gas emissions.

At the Department of Urban and Rural Development at SLU, there is an ongoing project that explores how Swedish companies and consumers perceive carbon offsetting through tree planting projects. I am part of this project as a research assistant and currently work on an academic article that partly is based on my thesis. If you are interested in or want to know more about carbon offsetting, you can find out more about the project here and you are also most welcome to read my thesis, which is available online.