By: Erik Bongcam-Rudloff, Professor of Bioinformatics at the Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, SLU

As climates change and populations increase, Artificial Intelligence (AI) will be a key player in Africa in the creation of technological innovations that will improve and protect crop yield and livestock.

The work creating technologies that allows computers and machines to function in an intelligent manner is known as Artificial Intelligence or AI. The advantages of using AI based devices or systems are their low error rate and huge analysis capacity. If properly coded the AI systems have incredible precision, accuracy, and speed. They can also work independently in many, for humans, hard conditions and environments. One of the most interesting areas where AI is breaking into is agriculture.

One area using AI and attracting a lot of attention is the area more known as “Precision Farming”. Precision Farming generates accurate and controlled technologies for water and nutrient management. It also gives optimal harvesting, planting times and produce solutions in many other aspects of modern agriculture.

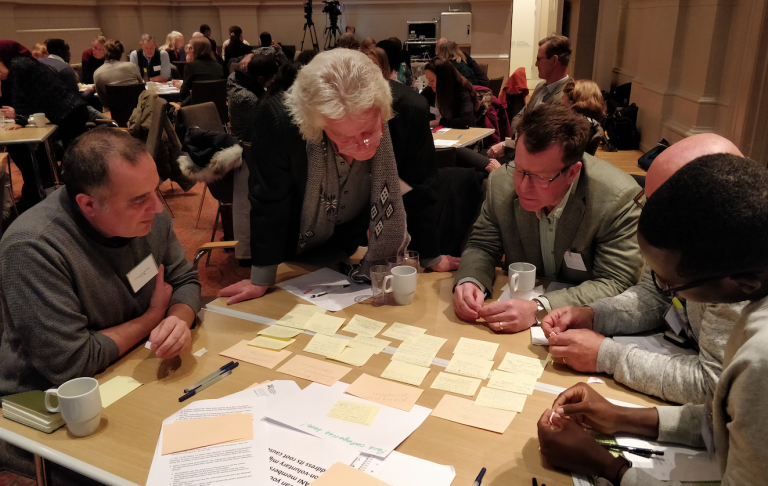

In April 2019 a workshop was held at Strathmore University, Nairobi in with the aim to set up a “Network of Excellence in Artificial Intelligence for Development in sub-Saharan Africa”. There where 60 international participants by invitation. The meeting was supported by Swedish SIDA and organised by the International Development Research Centre and Knowledge 4 Foundation (K4A).

The main goal of the workshop was to discuss the AI field with a bottom-up approach. The objectives of the workshop were to define the African Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence (ML/AI) landscape, to create an African research roadmap and to find ways to incorporate cross continental development. Around these objectives, four thematic areas of discussion were developed: governance, skills/capacity building, applications and others.

On the last day of the workshop we visited the IBM Research – Africa in Nairobi. The staff at IBM-Africa presented several AI projects and one example related to the future of AI in agriculture was presented by Juliet Mutahi, a software Engineer working at the IBM Nairobi THINKLab. She presented “Hello Tractor” a system comparable to Uber for taxi but in this case a system that allows farmers to share tractor resources by using an app on their smartphones. This is the kind of initiatives that are created in Africa as a bottom-up approach. Juliet told the audience that she got the idea to create this system inspired by the work and needs of her parents that are coffee farmers in Kenya.

While identifying the different AI actors in the African continent, another initiative stood out among many: the “Deep Learning Indaba” initiative. This is an annual meeting of the African machine learning community. In 2018 the meeting took place in Stellenbosch, South Africa and gathered 600 participants from many African countries. The next annual meeting will take place in Nairobi, Kenya in August 2019 and the aim for this year is to gather over 700 participants. This shows the strength and vitality for this area of research in the Africa continent.

Many issues connected to agriculture will in the future be better handled using machine learning and artificial intelligence because AI can automate tasks that require human-level intelligence or beyond. This makes solutions that integrate AI better than today’s technologies. Most researchers involved in development research will in the near future learn how to use and how to incorporate AI in their work. Our young colleagues in the “Deep Learning Indaba” community are showing the way. The work in creating the “Network of Excellence in Artificial Intelligence for Development in sub-Saharan Africa” is just one of the building blocks in this process and SLU will be part of it.

Watch an interview with Erik Bongcam-Rudloff talking about African bioinformatics and AI filmed at the Network of Excellence in Artificial Intelligence for Development in Nairobi, Kenya.