This is a blog post by Sanna Brithéll a master student in Environment, Politics, and Global Development and an intern at SLU Global, referencing her experiences on SIANI (The Swedish International Agricultural Network Initiative) and FOCALI’s (The Forest, Climate, and Livelihood research network) annual meetings 2025.

Did you know that there is a difference between agroecology and sustainable intensification[1]? Or that farmers in Kyrgyzstan not only carry the burden of providing food for the population, but also get subsidises from the state to use fertilisers? These are jut two examples of what was discussed that I thought were interesting out of everything that was brought up at SIANI’s Annual Meeting 2025. (By Klara Fischer, an associate professor in rural development at SLU, and Tatiana Stebneva, boars´d member at the Central Asia Solidarity Groups.)

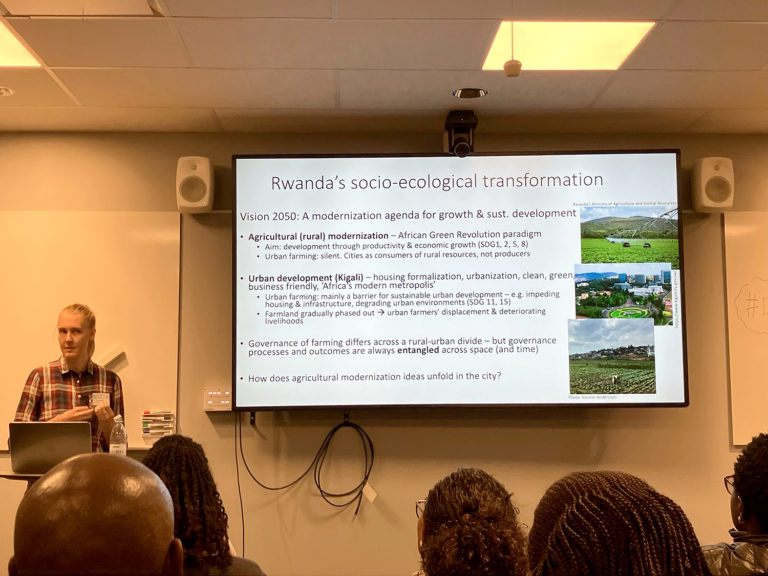

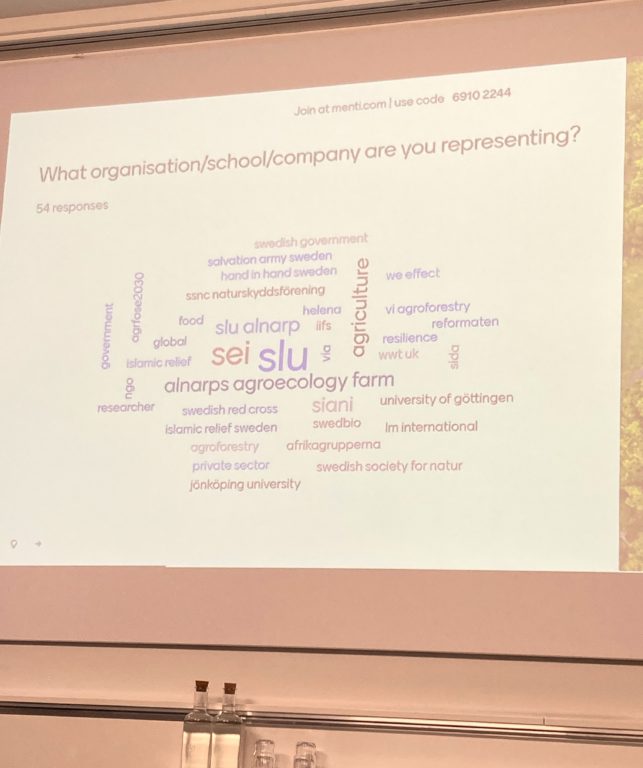

The event started out with encouraging people to write down what organisation they represented on Menti.com. It was very clear, looking at the results, that the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) had most of the votes. Paul Egan from SLU Global was even a part of the expert group discussion.

A picture of the Menti results from the question “what organisation/school/company are you representing” Photo: Sanna Brithéll

Apart from interesting speakers and networking, participants at each table were assigned to brainstorm ideas on what is needed or would be beneficial for the cause we are striving for; sustainable development. After we presented our ideas, we were given six stickers in two different colours. The red stickers were the most innovative and the green stickers the most important. I had the pleasure to get to present the most innovative ideas, alongside the others on the podium. This was because the group moderator thought I would be able to explain my own ideas, since most of them were selected.

The red arrows in the photo mark which ideas where mine. Photo: Sanna Brithéll

We had an interesting discussion at my table. You can see me sitting to the right in a black t-shirt. Photo borrowed from SIANI’s website.

Helene Forslund, a speaker from the Red Cross, used the word “empowerment,” which I felt perfectly captured the atmosphere at SIANI. She discussed the significance of the term in a different context, supporting vulnerable communities. She spoke about the fact that when one enters such a community, their goal should be to empower the people and not to “lead them”. This means shifting the mindset from expecting people to look up to or follow you, to instead focusing on helping them build their own connections. Your role is to provide the roadmap that enables them to do so. Respect is essential for a successful collaboration not only in these situations.

Marie Stenseke, brought this up as well and put it out beautifully at FOCALI “Interdisciplinary is like a dish, we are not the same ingredient, but we should be able to work together”

FOCALI had ongoing themes brought up by different researchers. They emphasised the needs for collaboration, the importance of finding synergies and having the ability to present that to decision makers and others important stakeholders. So, it was only fitting when the “IPBES Nexus Assessment Report”. Even though it was a summary, I felt it was important and relevant to the theme of synergies, because that is what the report presents. I know this because I read and summarised the whole report myself, to later be present it for my colleagues at SLU Global.

It was inspiring and fun to be present on both events. I got a lot of insights during the two days I participated, not only on the things presented or discussed but also the culture of academia.

If I had to take away one key insight from these events, it would be the importance of “getting dirt under my fingernails.” As Marie-Clair Feller, a student at SLU Alnarp, put it: “It’s a bit strange to learn about agriculture without knowing how to grow a carrot.”

[1] Fischer, K., Vico, G., Röcklinsberg, H., Liljenström, H. & Bommarco, R., 2025. Progress towards sustainable agriculture hampered by siloed scientific discourses. Nature Sustainability, 8, s. 66–74.