This blog is written by Ikhlass El Berbri, associate professor of animal infectious diseases at the Agronomy and Veterinary Institute Hassan II, Morocco.

Ikhlass El Berbri and Erik Bongcam-Rudloff in Rabat, Morocco.

The world is currently facing an anthropogenic climate crisis that is already impacting human health and is likely to do so in increasingly severe ways. Climate change effects on human health include heat-related mortality, a variety of health issues from natural disasters like flooding and droughts, food insecurity due to reduced crop yields, and a heightened risk for the transmission of infectious diseases and the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Furthermore, climate-induced changes in temperature and rainfall, along with extreme weather events, promote the proliferation of resistant bacterial strains and increase the need for antibiotics, compounding the problem of antibiotic resistance.

The emergence of multiple drug-resistant bacteria is indeed rising to dangerously high levels globally, severely undermining the effectiveness of available antibiotics. As a result, even minor injuries and routine medical procedures now pose serious risks due to antibiotic-resistant infections.

Escherichia coli is a common pathogen found consistently in the digestive tracts of animals and humans, as well as in the environment. Multidrug resistance in Escherichia coli has become a concerning issue, increasingly observed in both humans and veterinary medicine worldwide. E. coli is intrinsically susceptible to almost all clinically relevant antimicrobial agents, but this bacterial species has a great capacity to accumulate resistance genes, mostly through horizontal gene transfer. In recent years, E. coli has become one of the common bacterial sources to antimicrobial resistance genes, which has been prevalent and exhibited an increasing trend. One of the most important factors favouring this spread is ecosystems and climate deregulation, which cause human and animal populations to migrate and create novel transmission pathways for pathogens, including E. coli.

In this context, and to assess the role of the environment in the transmission and spread of resistant bacteria, our project aims to determine the genetic relatedness of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from animals and their environment.

With this regard, and to ensure that the results are thoroughly and effectively explored to understand the genetic mechanisms underlying this phenomenon, and in order to improve my skills in term of genomic sequencing and bioinformatics analysis, I have opted for a collaboration with a team with international renown researchers from the Department of Animal Sciences, Bioinformatics Section, led by Professor Erik Bongcam-Rudloff, at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). The team’s innovative work and collaborative environment offer a unique chance to explore the complexities of my research, using their expertise to improve my understanding of the outcomes of my results.

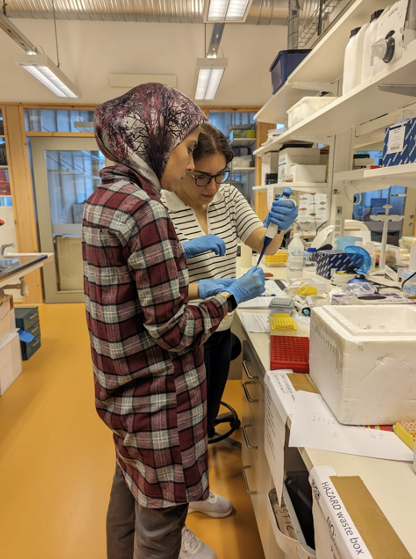

A photo capturing the essence of teamwork at the lab at SLU. Photo: Udeshika Sewwandi

During my stay at SLU, I gained a wealth of valuable knowledge and experience. I had the privilege of engaging with renowned experts in the field and built a strong network of contacts. These connections are very important for my academic journey and are also instrumental in facilitating future collaborations. Professor Erik Bongcam-Rudloff also visited the Veterinary Institute Hassan II in Morocco, where he delivered lectures and tutorials on bioinformatics for students and researchers. Following these productive exchanges of researchers between Sweden and Morocco, we are now prepared to launch new projects that leverage our combined expertise to address significant global health challenges.