Stabilising human urine before it hydrolyses has long been one of the more persistent operational challenges in urine-diverting sanitation systems. Our recently published study introduces a building-scale on-site reactor that passively doses freshly collected urine with sparingly soluble fumaric acid, offering a low-tech, cost-effective, and robust solution that complements front- and back-end innovations in urine source separation.

In contrast to soluble acids like citric or oxalic acid, which require continuous or precise metering to avoid oversaturation or pH swings, fumaric acid’s low solubility (6–11 g/L in urine) lends itself naturally to passive dosing. We developed a 5-L reactor where 250 g of fumaric acid was pre-loaded and gradually consumed as urine was incrementally added. Over 15 days, the system mimicked 263 urination events, treating 46 L of urine while maintaining pH < 4.0 for the majority of the experiment, successfully inhibiting urease activity and preventing mineral precipitation.

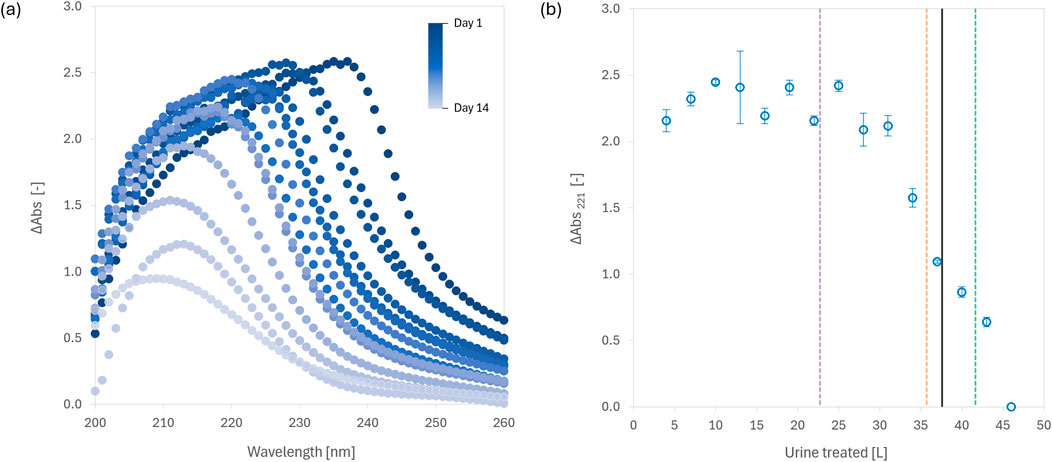

One of the more novel aspects of this study was our use of UV-Vis absorbance as a practical, real-time surrogate for process monitoring. ΔAbs221 was found to reliably track fumaric acid saturation and consumption in the reactor, providing earlier indication of reactor exhaustion than pH measurements. Similarly, ΔAbs660 was shown to be a useful proxy for assessing solids settling, particularly relevant when the fumaric acid transitions from supersaturated to undersaturated states.

From a design and scaling perspective, the passive dosing mechanism offers a number of practical advantages. There is no need for metering pumps or automation to control acid input. Fumaric acid can simply be pre-loaded in excess, creating a buffered environment where low pH is maintained until the acid is exhausted. This makes it ideal for decentralised or semi-centralised sanitation systems in public buildings or housing blocks. While the reactor in this study was operated under controlled lab conditions, the materials, energy input, and mixing protocols were deliberately chosen to mimic real-world use. The estimated operating cost—less than US$ 5 per person per year—compares favourably to existing benchmarks, including the Gates Foundation’s target for non-sewered sanitation solutions.

A key outcome of this study is that stabilised urine retained nitrogen in the form of urea, and did not exhibit significant losses in other key macronutrients—except for about 20% sulphate, which warrants further investigation. The system is therefore compatible with downstream processing aimed at nutrient concentration, e.g., evaporation or freeze-drying. Looking forward, integrating such a passive stabilisation reactor upstream of back-end treatment units could simplify plumbing, reduce pipe blockages, and improve user acceptance, particularly in building-scale deployments. When combined with turbidity sensors, occupancy-based drainage triggers, and modular back-end technologies, this approach offers a feasible path toward closing the loop on nutrient flows without increasing user burden or operational complexity.

The full article is available open access at Frontiers in Environmental Science: https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2025.1546396.

Hi! My name is Nathanaël, but everyone calls me Nate, so feel free to do the same. I am currently interning with the Environmental Engineering Research Group at SLU for three months, and I’ll be here until July 26th. I come from Strasbourg, France, where I attend ENGEES (National School of Water and Environmental Engineering, Strasbourg). Our focus is on all aspects of water, from the smallest water cycles to the bigger picture. Next school year will be my final year before I become an engineer. My specialty is water treatment, and I aspire to work in wastewater treatment plants or in a design office that deals with their dimensioning or startup. This interest led me to contact researcher Prithvi Simha, as I found the subject of urine separation particularly fascinating and underexplored at my school. I’m currently working and learning with PhD student Christoffer Parrow Melhus on urine collection pipes. In these pipes, urea breaks down into ammonia and carbon dioxide, leading to precipitation that can cause complete blockages. On a personal note, I enjoy discovering new things and was actively involved in student life at my school, organizing events for my peers. In my spare time, I like to go fishing to recharge my batteries.

Hi! My name is Nathanaël, but everyone calls me Nate, so feel free to do the same. I am currently interning with the Environmental Engineering Research Group at SLU for three months, and I’ll be here until July 26th. I come from Strasbourg, France, where I attend ENGEES (National School of Water and Environmental Engineering, Strasbourg). Our focus is on all aspects of water, from the smallest water cycles to the bigger picture. Next school year will be my final year before I become an engineer. My specialty is water treatment, and I aspire to work in wastewater treatment plants or in a design office that deals with their dimensioning or startup. This interest led me to contact researcher Prithvi Simha, as I found the subject of urine separation particularly fascinating and underexplored at my school. I’m currently working and learning with PhD student Christoffer Parrow Melhus on urine collection pipes. In these pipes, urea breaks down into ammonia and carbon dioxide, leading to precipitation that can cause complete blockages. On a personal note, I enjoy discovering new things and was actively involved in student life at my school, organizing events for my peers. In my spare time, I like to go fishing to recharge my batteries.