Hi, my name’s Nicola Parfitt and I recently spent a wonderful week on Gotland interviewing farmers about their perceptions of human urine as a fertilizer. I did this as part of my master thesis in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science at Lund University, which I can’t believe is already coming to an end in June.

Hi, my name’s Nicola Parfitt and I recently spent a wonderful week on Gotland interviewing farmers about their perceptions of human urine as a fertilizer. I did this as part of my master thesis in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science at Lund University, which I can’t believe is already coming to an end in June.

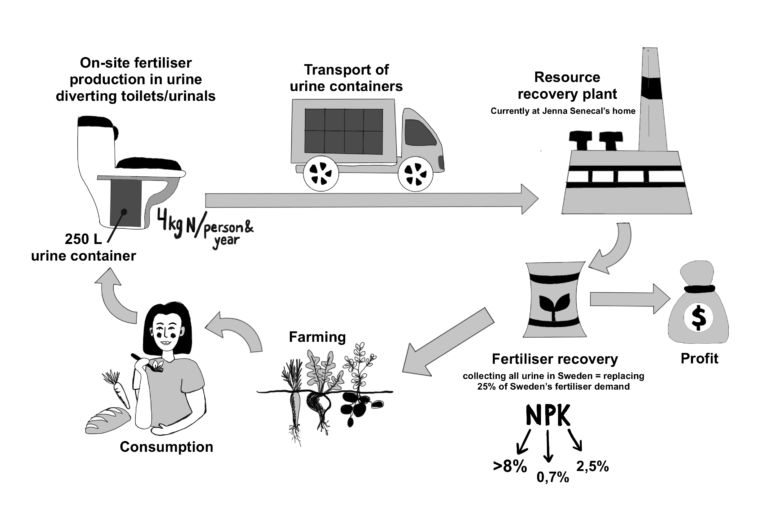

I came into contact with this topic after Jenna Senecal, the CEO of Sanitation360 who recycles human urine and turns it into a fertilizer on Gotland, held a lecture as part of one of the courses I was taking. The potential of ecological sanitation and nutrient recycling to reduce eutrophication, contribute to circular farming and also provide decentralized toilets in countries where access to basic sanitation facilities is still low, made me fall in love with the concept. However, for the loop between sanitation and agriculture to be fully closed, farmers need to be willing to use the end product – and that’s how my thesis idea came about.

From my discussions with nine grain and/or vegetable farmers on Gotland (both conventional, KRAV-certified and EU-organic) I learned that all farmers knew about the potential to use human urine as a fertilizer but were surprised it was allowed in conventional farming in Sweden. In terms of prior use, the two farmers who had used urine in some way for years (through fertigation or their own sewage well) were the only ones not worried about consumer acceptance as they trusted the safety and quality of urine. This showcases the importance of combining frequent soil testing with the use of the fertilizer, especially during its first years on the market. However, soil mapping was seen as more of a necessity to receive EU funding and follow regulations than to inform fertilizer use, also due to how expensive testing is. Therefore, while urine diverting toilets and urinals will contribute to reducing eutrophication from the sanitation sector, the use of human urine as a fertilizer will not necessarily reduce eutrophication from agriculture as it is simply another fertilizer that can be used. Therefore, it needs to be combined with nutrient management education and more frequent soil testing in order to further reduce eutrophication from agriculture.

No farmers were either disgusted with the idea of using it but were worried consumers would be. The negative media portrayal that sludge has received in Sweden in recent decades, along with worries about consumers finding the use of urine disgusting, were expressed as barriers for farmers to adopt urine fertilizers. Some farmers thought it might be best to use it for non-food crops instead, such as bioenergy or livestock feed crops, as they worry about the health implications hazardous substances could have if it isn’t possible to fully remove those substances from urine. These worries have caused a low interest amongst farmers to actively seek out fertilizers made from human excreta, suggesting a need for Gotlandic and other Swedish farmers to be approached by fertilizer retailers, agricultural agencies or the government in order to become aware that it’s even an option on the market. In tandem, consumer acceptance will likely be a big obstacle to overcome for farmers to feel comfortable using human urine as a fertilizer.

On the bright side, its circular properties were seen as very beneficial and all farmers stressed the importance of creating a circular system between cities and agriculture, which their current fertilizers do not contribute to. There was also a shared sense of relief amongst all farmers that Sanitation360 was aiming to fully produce its fertilizer on Gotland, which can be seen in this quote from one of the farmers who expressed that it was costly with farm inputs when you live on a small island:

“When you live on Gotland you’re punished twice because you pay for shipping when you order things and there is so much we need to buy but no company on Gotland who produces the things we need.”

The dry-pelleted form was also seen as beneficial as it is compatible with most farmers’ machinery and is more nutrient dense per unit of weight in comparison to liquid urine, making it easier to store, transport and handle. However, converting raw urine into a dry form also makes it more energy intensive and costly to produce, which could lead to inequalities in terms of who will be able to afford the fertilizer. A previous study on the use of raw urine by smallholder farmers in Uganda found that the fact that urine was a free resource to use as a fertilizer was one of its most beneficial aspects (Andersson, 2015). This was also reflected on by the farmer who already used wastewater for irrigation and by vegetable farmers who said they would appreciate a liquid fertilizer for their drop irrigation system in their greenhouses.

The need for specific NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) ratios could also hinder adoption as grain farmers want much higher nitrogen concentrations than Sanitation360 currently manages to recover and vegetable farmers want much higher potassium levels. They saw no issue with the low phosphorus levels in the fertilizer which is due to the naturally high phosphorus levels in Gotlandic soil. However, in places where phosphorus levels aren’t naturally high, it is important for human urine fertilizers to be offered in other NPK ratios to fit different production orientations and soils.

My interviews suggest that farmers have a lot to say and contribute to in terms of the development of human urine fertilizers and including them in the process is important to facilitate a smooth transition to a circular nutrient economy. Sanitation360’s fertilizer has big potential to contribute to this circular nutrient transition on Gotland and lead the way for other parts of the world too!

I’m so grateful to the farmers for welcoming me into their homes and being so willing to talk about this, unfortunately, tabu topic. I had such a lovely week on Gotland with Jenna and her family and can’t wait to go back for Sanitation360’s demo day on the 13th of June. Hope to see you there!

References:

Andersson, E. (2015). Turning waste into value: Using human urine to enrich soils for sustainable food production in Uganda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 96, 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.070